Greek Coins 5 Drachmes 1998 Aristotle

Obverse: The portrait in left profile of Aristotle (384 - 322 BC), a Greek philosopher, a student of

Plato and teacher of

Alexander the Great, is surrounded with a legend which indicates his name in Greek: "ΑΡΙΣΤΟΤΕΛΗΣ".

Lettering: ΑΡΙΣΤΟΤΕΛΗΣ.

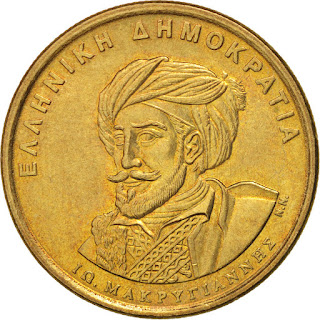

Reverse: The facial value according to the new spelling ("5 ΔΡΑΧΜΕΣ") is encircled by the inscription "ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ" (Republic of Greece).

Lettering: 5 ΔΡΑΧΜΕΣ • 1998 • ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑ.

Edge: Smooth.

Years: 1982-2000.

Value: 5 Drachmes (5 GRD).

Metal: Copper-nickel.

Weight: 5.5 g.

Diameter: 22.5 mm.

Thickness: 1.85 mm.

Shape: Round.

Aristotle

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was born circa 384 B.C. in Stagira, Greece. When he turned 17, he enrolled in Plato’s Academy. In 338, he began tutoring Alexander the Great. In 335, Aristotle founded his own school, the Lyceum, in Athens, where he spent most of the rest of his life studying, teaching and writing. Aristotle died in 322 B.C., after he left Athens and fled to Chalcis.

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was born circa 384 B.C. in Stagira, a small town on the northern coast of Greece that was once a seaport. Aristotle’s father, Nicomachus, was court physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas II. Although Nicomachus died when Aristotle was just a young boy, Aristotle remained closely affiliated with and influenced by the Macedonian court for the rest of his life. Little is known about his mother, Phaestis; she is also believed to have died when Aristotle was young.

After Aristotle’s father died, Proxenus of Atarneus, who was married to Aristotle’s older sister, Arimneste, became Aristotle’s guardian until he came of age. When Aristotle turned 17, Proxenus sent him to Athens to pursue a higher education. At the time, Athens was considered the academic center of the universe. In Athens, Aristotle enrolled in Plato’s Academy, Greek’s premier learning institution, and proved an exemplary scholar. Aristotle maintained a relationship with Greek philosopher Plato, himself a student of Socrates, and his academy for two decades. Plato died in 347 B.C. Because Aristotle had disagreed with some of Plato’s philosophical treatises, Aristotle did not inherit the position of director of the academy, as many imagined he would.

After Plato died, Aristotle’s friend Hermias, king of Atarneus and Assos in Mysia, invited Aristotle to court. During his three-year stay in Mysia, Aristotle met and married his first wife, Pythias, Hermias’ niece. Together, the couple had a daughter, Pythias, named after her mother.

Teaching

In 338 B.C., Aristotle went home to Macedonia to start tutoring King Phillip II’s son, the then 13-year-old Alexander the Great. Phillip and Alexander both held Aristotle in high esteem and ensured that the Macedonia court generously compensated him for his work.

In 335 B.C., after Alexander had succeeded his father as king and conquered Athens, Aristotle went back to the city. In Athens, Plato’s Academy, now run by Xenocrates, was still the leading influence on Greek thought. With Alexander’s permission, Aristotle started his own school in Athens, called the Lyceum. On and off, Aristotle spent most of the remainder of his life working as a teacher, researcher and writer at the Lyceum in Athens.

Because Aristotle was known to walk around the school grounds while teaching, his students, forced to follow him, were nicknamed the “Peripatetics,” meaning “people who travel about.” Lyceum members researched subjects ranging from science and math to philosophy and politics, and nearly everything in between. Art was also a popular area of interest. Members of the Lyceum wrote up their findings in manuscripts. In so doing, they built the school’s massive collection of written materials, which by ancient accounts was credited as one of the first great libraries.

In the same year that Aristotle opened the Lyceum, his wife Pythias died. Soon after, Aristotle embarked on a romance with a woman named Herpyllis, who hailed from his hometown of Stagira. According to some historians, Herpyllis may have been Aristotle’s slave, granted to him by the Macedonia court. They presume that he eventually freed and married her. Regardless, it is known that Herpyllis bore Aristotle children, including one son named Nicomachus, after Aristotle’s father. Aristotle is believed to have named his famed philosophical work Nicomachean Ethics in tribute to his son.

When Aristotle’s former student Alexander the Great died suddenly in 323 B.C., the pro-Macedonian government was overthrown, and in light of anti-Macedonia sentiment, Aristotle was charge with impiety. To avoid being prosecuted, he left Athens and fled to Chalcis on the island of Euboea, where he would remain until his death.

Science

Although Aristotle was not technically a scientist by today’s definitions, science was among the subjects that he researched at length during his time at the Lyceum. Aristotle believed that knowledge could be obtained through interacting with physical objects. He concluded that objects were made up of a potential that circumstances then manipulated to determine the object’s outcome. He also recognized that human interpretation and personal associations played a role in our understanding of those objects.

Aristotle’s research in the sciences included a study of biology. He attempted, with some error, to classify animals into genera based on their similar characteristics. He further classified animals into species based on those that had red blood and those that did not. The animals with red blood were mostly vertebrates, while the “bloodless” animals were labeled cephalopods. Despite the relative inaccuracy of his hypothesis, Aristotle’s classification was regarded as the standard system for hundreds of years.

Marine biology was also an area of fascination for Aristotle. Through dissection, he closely examined the anatomy of marine creatures. In contrast to his biological classifications, his observations of marine life, as expressed in his books, are considerably more accurate.

As evidenced in his treatise Meteorology, Aristotle also dabbled in the earth sciences. By meteorology, Aristotle didn’t simply mean the study of weather. His more expansive definition of meteorology included “all the affectations we may call common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the earth and the affectations of its parts.” In Meteorology, Aristotle identified the water cycle and discussed topics ranging from natural disasters to astrological events. Although many of his views on the Earth were controversial at the time, they were readopted and popularized during the late Middle Ages.

Philosophy

One of the main focuses of Aristotle’s philosophy was his systematic concept of logic. Aristotle’s objective was to come up with a universal process of reasoning that would allow man to learn every conceivable thing about reality. The initial process involved describing objects based on their characteristics, states of being and actions. In his philosophical treatises, Aristotle also discussed how man might next obtain information about objects through deduction and inference. To Aristotle, a deduction was a reasonable argument in which “when certain things are laid down, something else follows out of necessity in virtue of their being so.” His theory of deduction is the basis of what philosophers now call a syllogism, a logical argument where the conclusion is inferred from two or more other premises of a certain form.

In his book Prior Analytics, Aristotle explains the syllogism as “a discourse in which, certain things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so.” Aristotle defined the main components of reasoning in terms of inclusive and exclusive relationships. These sorts of relationships were visually grafted in the future through the use of Venn diagrams.

Aristotle’s philosophy not only provided man with a system of reasoning, but also touched upon ethics. In Nichomachean Ethics, he prescribed a moral code of conduct for what he called “good living.” He asserted that good living to some degree defied the more restrictive laws of logic, since the real world poses circumstances that can present a conflict of personal values. That said, it was up to the individual to reason cautiously while developing his or her own judgment.

Major Writings

Aristotle wrote an estimated 200 works, most in the form of notes and manuscript drafts. They consist of dialogues, records of scientific observations and systematic works. His student Theophrastus reportedly looked after Aristotle’s writings and later passed them to his own student Neleus, who stored them in a vault to protect them from moisture until they were taken to Rome and used by scholars there. Of Aristotle’s estimated 200 works, only 31 are still in circulation. Most date to Aristotle’s time at the Lyceum.

Aristotle’s major writings on logic include Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics and Posterior Analytics. In them, he discusses his system for reasoning and for developing sound arguments.

Aristotle’s written work also discussed the topics of matter and form. In his book Metaphysics, he clarified the distinction between the two. To Aristotle, matter was the physical substance of things, while form was the unique nature of a thing that gave it its identity.

Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics are Aristotle’s major treatises on the behavior and judgment that constitute “good living.” In Politics, Aristotle examined human behavior in the context of society and government.

Aristotle also composed a number of works on the arts, including Rhetoric, and science, including On the Heavens, which was followed by On the Soul, in which Aristotle moves from discussing astronomy to examining human psychology. Aristotle’s writings about how people perceive the world continue to underlie many principles of modern psychology.

Death and Legacy

In 322 B.C., just a year after he fled to Chalcis to escape prosecution under charges of impiety, Aristotle contracted a disease of the digestive organs and died. In the century following his passing, his works fell out of use, but were revived during the first century. Over time, they came to lay the foundation of more than seven centuries of philosophy. Solely regarding his influence on philosophy, Aristotle’s work influenced ideas from late antiquity all the way through the Renaissance. Aristotle’s influence on Western thought in the humanities and social sciences is largely considered unparalleled, with the exception of his teacher Plato’s contributions, and Plato’s teacher Socrates before him. The two-millennia-strong academic practice of interpreting and debating Aristotle’s philosophical works continues to endure.